The board calendar is full. Another AI steering committee. Another risk review. Another escalation waiting for the next meeting slot.

Meanwhile, the model has already been retrained twice. The product team has moved on. And somewhere in the business, an employee has quietly adopted an unsanctioned tool to get the job done faster.

This is the governance paradox of the AI era: in trying to reduce risk, organisations are often slowing transformation and sometimes increasing exposure in the process.

Governance Designed for Control, Not Velocity

Enterprises are not wrong to take AI governance seriously. The regulatory landscape is tightening. Boards are being asked questions they cannot easily answer. The EU AI Act requires deployers of high-risk systems to monitor operation, retain logs and ensure human oversight. ISO/IEC 42001 frames AI governance as a management system requiring continual improvement. NIST’s AI Risk Management Framework similarly embeds governance across the lifecycle.

In response, organisations have built steering boards, ethics panels, design authorities and risk councils. Public-sector audits show similar patterns: layered governance structures, multiple review groups, and consultation forums.

The intent is rational. AI introduces opacity, drift, bias and security risk. Oversight is necessary.

The problem emerges when oversight becomes episodic and committee-centric, when governance is structured around meetings rather than systems.

Research from McKinsey & Company shows only 48% of organisations believe they make decisions quickly, and just 37% report decisions that are both high quality and high velocity. Now place AI delivery, iterative, continuous, often weekly, into that environment. Decision latency becomes structural.

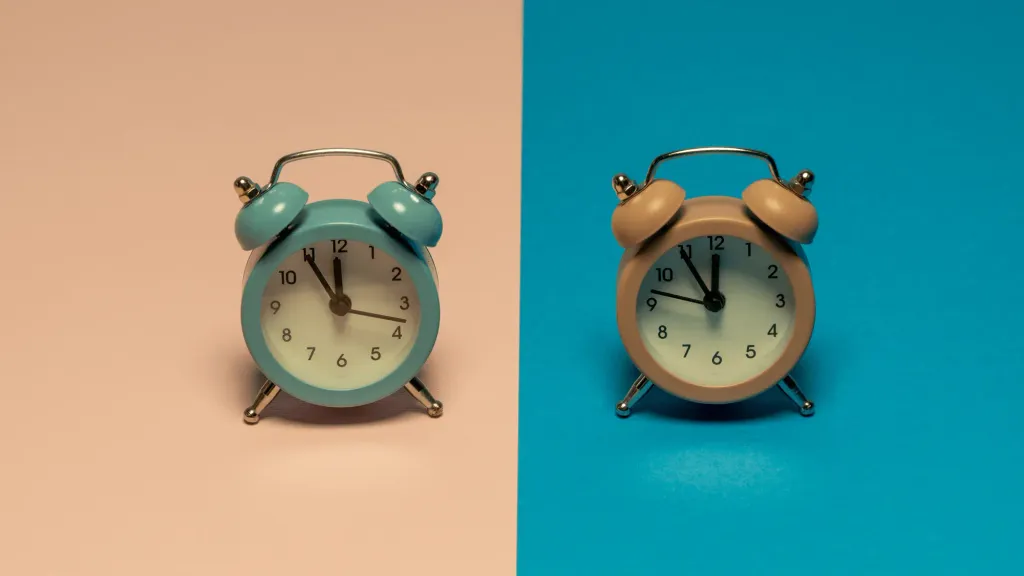

Board committees typically meet seven to eight times a year. AI models, by contrast, can be retrained daily. Product releases move in days, not quarters. When every material AI change requires formal review, governance becomes a queue.

And queues compound.

The Decision Latency Effect

The DevOps Research and Assessment programme (DORA) has long studied change approval boards. Its findings are uncomfortable: heavyweight external approvals negatively impact delivery performance and show no evidence of reducing failure rates.

Slowing delivery increases batch size. Larger batches increase blast radius when something goes wrong. In other words, more gates can create more risk.

The analogy to AI governance is direct. When approval cycles stretch, teams delay releases. Changes accumulate. Escalations stack up. By the time approval arrives, context has shifted.

Meanwhile, adoption does not wait.

Microsoft’s Work Trend Index reports that 78% of AI users bring their own AI tools to work. Salesforce found that over half of employees using generative AI at work did so without formal employer approval. Slack data shows quarter-over-quarter acceleration in AI tool adoption.

Governance friction does not suppress usage. It redirects it.

And the external risk signal is rising. The Stanford AI Index recorded 233 reported AI incidents in 2024, a 56% increase year on year. At the same time, business AI usage accelerated sharply across organisations. Risk surface is expanding faster than oversight maturity.

This is the committee trap: governance activity increases, yet effective control does not.

Oversight Versus Ownership

There is another structural issue. Committees multiply veto points. Decision rights blur.

Research on organisational performance highlights predictable bottlenecks when decision authority is unclear. AI governance often introduces precisely this ambiguity: multiple leaders jointly “own” AI. McKinsey reports that organisations average two leaders responsible for AI governance, with varying levels of CEO and board oversight.

Without clear tiers, everything escalates.

Contrast this with firms redesigning governance for flow rather than friction. Morgan Stanley appointed a firmwide head of AI to coordinate strategy across functions. GSK established a cross-functional AI Governance Council paired with distributed execution standards. Uber embedded model quality metrics and lifecycle monitoring directly into platform operations.

The pattern is consistent: committees define guardrails and principles. Platforms enforce them continuously.

Governance becomes architectural, not procedural.

What High-Performing Governance Looks Like

Evidence suggests transformation succeeds when oversight shifts from gates to guardrails.

Risk tiering is central. MIT Sloan describes “traffic light” governance models, matching oversight depth to risk class. Not every use case needs board escalation. Universal sign-off creates universal delay.

Automation replaces manual inspection. DORA argues approvals should be embedded through peer review, automated testing and monitoring rather than external queues. In AI terms, that means evaluation harnesses, logging, policy-as-code, audit trails and runtime observability.

Continuous assurance replaces episodic review. The EU AI Act emphasises operational monitoring and logging. ISO 42001 requires continual improvement. These are system behaviours, not meeting agendas.

Most importantly, decision rights must be explicit. Who approves low-risk changes? Who can pause a deployment? Who owns runtime performance? Without clarity, committees expand by default.

The economic stakes are growing. Boston Consulting Group reports that only 5% of firms capture AI value at scale, while 60% achieve minimal material impact. Agentic AI already accounts for 17% of AI value in 2025 and is projected to rise sharply. As autonomy increases, governance delay becomes more expensive.

The Human Dimension

If you are a CIO or CISO, the risk is not that governance exists. It is that governance feels active while value stalls.

Your teams wait for approval while shadow tools proliferate. Your board requests assurance while operational monitoring remains immature. Your risk committees expand even as adoption accelerates beyond their line of sight.

The instinct to add oversight is understandable. Deloitte research shows many boards still have limited AI literacy. Committees create visible accountability.

But visibility is not velocity. And velocity now matters.

AI systems learn weekly. Customer expectations shift daily. If governance cannot operate at comparable cadence, transformation fragments. High-performing teams adapt through sanctioned pathways. Others bypass.

The outcome is uneven risk exposure, precisely what governance was meant to prevent.

The Real Question

The question is not how to reduce governance. It is how to redesign it.

How much governance is enough, and how much is too much?

The answer lies in architecture, not attendance. Risk-tiered models. Embedded controls. Clear decision rights. Continuous monitoring. Committees that set standards and intervene strategically, rather than review every prompt and parameter.

Oversight remains essential. The rise in AI incidents proves that under-governance is not theoretical. But control theatre is equally dangerous.

In an AI-first organisation, governance must move from periodic approval to operational discipline. From meeting cadence to system cadence.

Because when AI cycles move weekly and governance moves quarterly, value does not slow down.

It leaks.