The Signal Behind the Surge

Last year, a global technology firm quietly disclosed that it had ingested flawed customer data into its AI training pipeline. The result was not a marginal performance dip but an estimated nine-figure financial impact. The instinct had been simple: feed the system more data, improve the model, scale the gains. Instead, volume amplified weakness.

It was a reminder that in enterprise AI, accumulation is not the same as strategy. And as AI systems move from experimentation into operational decision loops, that distinction becomes structural.

Data Volume Is Not a Business Strategy

There is a persistent belief in boardrooms and product teams: when AI underperforms, the solution is to collect more data. More examples. More tokens. More history. More signals.

That belief is not entirely irrational. Early deep learning breakthroughs were fuelled by scale. Research into scaling laws demonstrated that model performance improves predictably as model size, dataset size, and compute increase together. Compute-optimal training research later showed that undertrained large models could be outperformed by better-balanced data and parameter allocation.

But those findings have been misread as an enterprise doctrine.

The frontier pre-training of large language models is not the same as shipping AI inside complex organisations. In enterprise environments, underperformance rarely stems from insufficient volume. It stems from structure: fragmented systems, inconsistent schemas, label noise, stale features, and misaligned objectives.

Evidence increasingly shows that beyond a certain point, indiscriminate scale produces diminishing returns, and sometimes regression.

Research presented at NeurIPS demonstrated that careful dataset curation can yield 18-20% training efficiency gains and measurable downstream performance improvements, while repeating random data can degrade outcomes. In other words, more tokens can make a system worse when they amplify noise rather than signal.

Another major ACL study found that common large-scale language model corpora contain significant duplication, and that deduplication reduced memorisation by tenfold while preserving or improving accuracy. Large datasets often carry structural repetition, contamination, and low-value artefacts that distort learning.

Volume is an input. It is not a strategy.

When Scale Amplifies Error

The risks of scale without structure are not theoretical.

Google Flu Trends famously relied on massive search query datasets to predict influenza prevalence. Yet it overestimated flu levels for 100 out of 108 weeks during one period and overshot actual rates by more than 50% in a single season. The failure was not caused by insufficient data. It was caused by drift, correlation without causation, and an objective misaligned with ground truth.

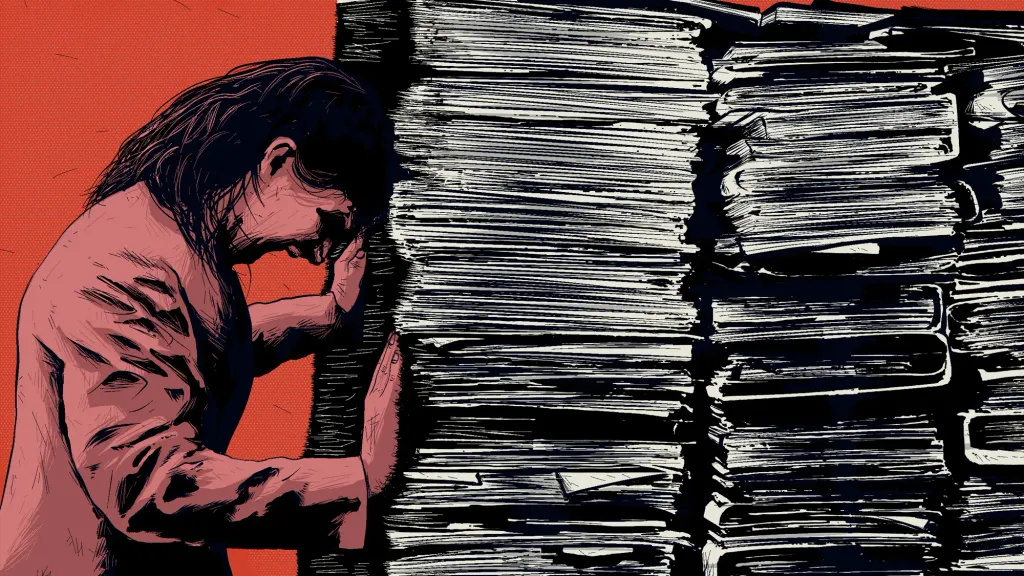

Unity Software disclosed that ingesting problematic customer data degraded the value of part of its training pipeline, contributing to an estimated $110 million impact. Again, the issue was not scarcity. It was governance.

Label noise research shows similar fragility. Studies have identified meaningful levels of label error in benchmark datasets, with modest noise increases capable of inverting performance advantages between larger and smaller models. In high-noise regimes, capacity magnifies confusion.

In enterprise systems, these issues compound. Salesforce research reports that the average enterprise runs hundreds of applications, with only a fraction meaningfully integrated. Data exists, but it is semantically inconsistent and operationally siloed. Adding more of it rarely fixes fragmentation.

Meanwhile, Gartner warns that poor data quality costs organisations millions annually and that most of the AI projects risk abandonment if not supported by AI-ready data practices.

The pattern is clear. AI systems inherit every structural weakness in the data layer. Increasing volume does not neutralise those weaknesses. It often accelerates them.

The Strategic Inflection Point

For technology leaders, this marks a shift from accumulation to engineering.

If your AI roadmap is framed around “acquiring more data,” you are optimising an asset inventory, not an intelligence system. Intelligence depends on relevance, freshness, semantic clarity, and alignment with outcomes.

Data minimisation principles under GDPR require that personal data be relevant and limited to what is necessary. The EU AI Act similarly mandates dataset relevance and governance for high-risk systems. Regulatory direction reinforces what operational evidence already suggests: indiscriminate expansion increases compliance burden without guaranteeing performance gains.

At the same time, research on feature staleness demonstrates that outdated signals degrade predictive quality over time. Freshness often matters more than historical depth.

In practice, this means AI advantage shifts from “how much data do we have?” to “how engineered is our data supply chain?”

Data contracts. Schema discipline. Deduplication. Objective alignment. Feedback loops tied to real outcomes rather than proxy metrics. These are strategic levers.

Smaller, curated datasets have repeatedly shown outsized impact. Microsoft's phi-1 model achieved competitive coding benchmarks using carefully selected and synthetic “textbook-quality” data rather than web-scale scraping. The LIMA study demonstrated that alignment quality could be driven by just 1,000 curated demonstrations.

These are not arguments for less data. They are arguments for intentional data.

The Human Dimension

Inside organisations, the belief that “more data fixes it” is psychologically comforting. It frames AI improvement as a procurement problem rather than a systems problem. Acquire more signals. Increase storage. Expand pipelines.

But if you are responsible for outcomes, customer decisions, risk assessments, pricing engines, you know that errors rarely announce themselves as data shortages. They surface as subtle drift, proxy distortion, or silent bias.

When your AI system recommends the wrong credit decision, misroutes a customer, or overestimates demand, the root cause is usually upstream: ambiguous ownership, stale definitions, ungoverned ingestion, or misaligned objectives.

More data can bury those signals deeper.

As AI systems take on autonomous roles, the cost of misalignment rises. A flawed recommendation engine is inconvenient. A flawed decision loop embedded in operations is structural risk.

The leadership challenge is not expanding volume. It is reducing ambiguity.

What Happens Next

The organisations that succeed in the next phase of enterprise AI will treat data as an engineered product, not a harvested commodity.

They will measure cost per signal, not terabytes stored. They will invest in freshness and semantic consistency before expanding acquisition. They will align training objectives with business intent rather than proxy metrics. They will design governance into ingestion rather than audit it retrospectively.

Volume still matters, but only within a disciplined architecture of relevance and accountability.

Training data is an ingredient. It is not a strategy.

The advantage will belong to leaders who understand that intelligence is shaped less by how much you feed a system, and more by how deliberately you design what it learns.